Party: Cory Olson, Dave Hobson, Lisa Wilkinson, Erin Low, Kelsey Low, Greg Horne, Fauve Blanchard, Felix Ossig-Bonanno, Chuck Priestley, Jurgen Deagle, Mike Kelly, Jason Headley, Dave Critchley, Imogen Grant-Smith

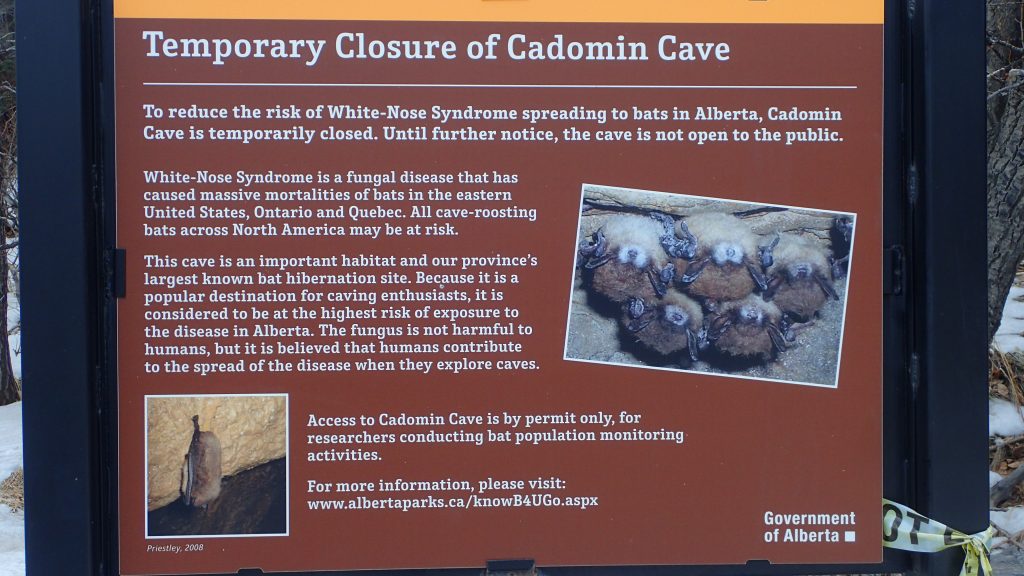

Firstly it is important to note that Cadomin Cave is currently closed to reduce risk of spreading White-Nose Syndrome, in particular to bats in Alberta. Access to Cadomin Cave is by permit only, for researchers conducting bat population monitoring activities.

WNS is a fungal disease that has caused massive mortalities of bats in the eastern United States, Ontario and Quebec. All cave-roosting bats across North America may be at risk.

This cave is an important habitat and our province’s largest known bat hibernation site. Because it is a popular destination for caving enthusiasts, it is considered to be at the highest risk of exposure to the disease in Alberta. The fungus is not harmful to humans, but it is believed that humans contribute to the spread to the disease when they explore caves.

It was almost a typical 7am start sitting out the front of the apartment as my colleagues jumped onto the work busses, but unlike a regular work day I was waiting for the car pool I had arranged with Greg and Jurgen. Only a few days earlier I had received an email from Greg inviting me to help out on a bat radio telemetry project headed by the Wildlife Conservation Society. The main goal of the trip would be to attach temperature-sensitive radio transmitters to about 15 bats.

We continued the rest of the way to the small mining town of Cadomin (an acronym for Canadian Dominion Mining). On the way Jurgen talked about about how popular amongst hunters the narrow strip of land between the mine and the National Park was. So popular that there are now only two hunting permits each season.

Once at the parking lot we spent some time sorting gear. There was a lot to carry, with the large batteries that power the receiver weighing a total of 200kg!

With snow shoes strapped to our packs we headed up the trail, stripping off layers as we went. As the snow deepened the snow shoes were donned. The trail become steeper and steeper as we neared the entrance. The last section was quite challenging, with the snow sliding below a slight wind slab, forcing you to kick in several times to get purchase on something solid.

We were glad to reach the cave entrance. All the cave gear needed to be decontaminated before entering the cave. If gear has been within about 200km of a known or suspected white-nose zone, then it should not go to the cave. (WNS is probably present near, or within, southern BC and eastern Manitoba. See here and here for more information.)

Steps were kicked into the snow bank sloping down into the entrance, and a hand line was rigged for those who wanted it, before the gear was relayed into the twilight zone.

We filtered into the West Gallery, keeping very quiet so we wouldn’t disturb the bats. The hope was that there would be enough that could be reached so we wouldn’t have to retrieve bats from the Turbine, an area further into the cave that requires some basic climbing to access. As we all scouted around it appeared there were enough low hanging bats and collection began (it is recommended that if you are handling bats you should have had the rabies vaccination and an up-to-date rabies titer check).

At this point, Dave led a small group (including myself) to continue the bat count. We continued down the Main Galley, down into the Turbine Passage, and then into the Mess Hall. Whilst down in the Turbine, Dave told us that the oldest known bat in North America had roosted in this chamber.

This little brown bat was banded by Dave Schowalter on the 21st of October 1975 as an adult. He was last seen on 27th January 2013. That would have made him at least 39 years old when last seen. The oldest bat that I’ve found a record of was a Russian Myotis sp. that was 41 years old.

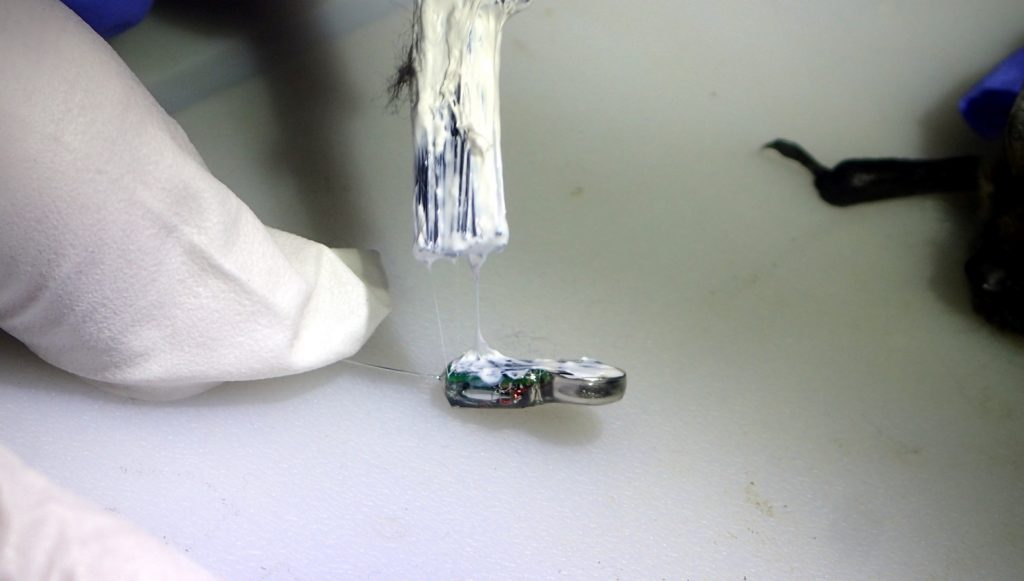

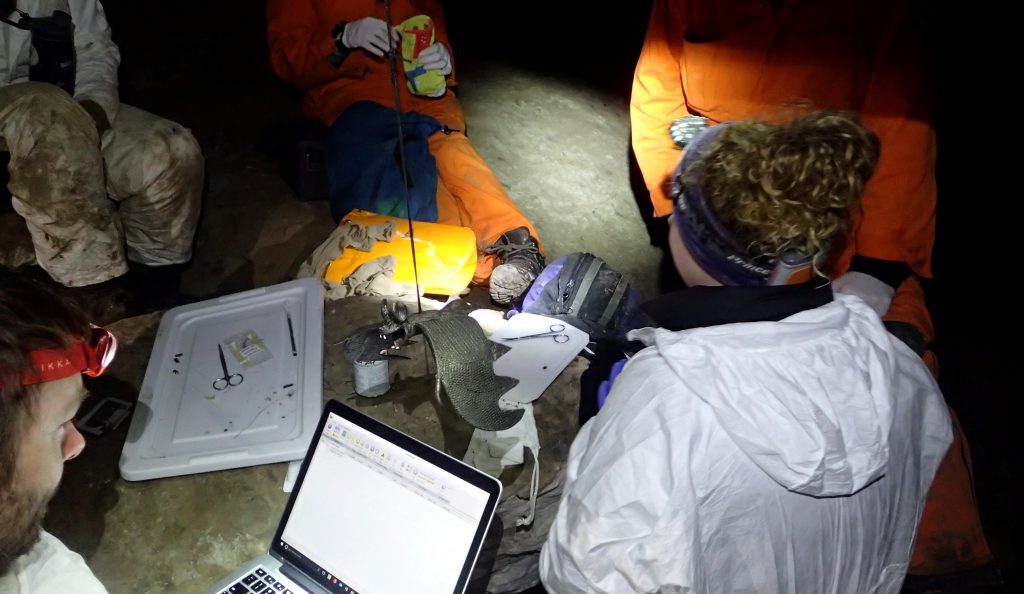

The bats were becoming a little active in the Mess Hall, so I decided to head back to minimise any disturbance. The rest of the team was now working at a makeshift office in the twilight zone. To attach the transmitters the bats received a small hair cut on their back. Glue was then applied to the bat as well as the transmitter. Once the glue had cured a little they were pressed together lightly for a while. The bat was then wrapped gently in a small piece of fabric and placed back into its cloth bag.

As well as attaching the transmitters, DNA swabs were taken, forearm lengths measured, sex determined, and teeth sharpness assessed. The transmitter frequencies also needed to be programmed into the receiver.

While this process was being finished off, half of us went back into the West Gallery to begin setting up the receiver station and ensuring it was protected against the pack rats (I had one eat through my pack in Pink Hole so understood the concern. I’d also seen one when we first entered the cave that morning.)

With everything looking like it was good to go we released the bats and held our breath.

Unfortunately, it seemed the range of the transmitters / receiver was worse than expected. We changed the antenna, but in the end resorted to relocating the receiver station deeper into the gallery. Everyone was getting quite tired by this point.

It was around 10:20pm when we got back to the cars. And well after midnight by the time those of us from Jasper were back home. Thankfully I slept for much of the drive. It was a fun trip, and a great opportunity to learn new skills.

References: