The day after the rescue of Jamie Neale, the English teenager lost for almost two weeks in the Blue Mountains, I spent a night retracing part of his route. The following story ran in the Daily Telegraph on July 18, 2009.

Setting off on Thursday afternoon, a chill was already in the air as I began my descent deep into the Blue Mountains bush. It was with some trepidation that I began my quest for a greater insight into the incredible survival of 19-year-old Jamie Neale, who spent 12 long days and freezing nights lost in an area containing some incredibly rugged terrain.

His walk would be impossible to replicate, but I was determined to try to capture both the harsh reality of the wilderness that entrapped him and glimpse the incredible fear, hopelessness and desperation he had felt.

With this in mind, I made my way through the Jamison Valley, past the Ruined Castle where Neale was last seen, and along the small, fern-lined track that leads to Mount Solitary.

Somewhere in this area just over a kilometre long Neale lost his way in the darkness, veered south towards Cedar Creek, and began his terrifying ordeal.

I paused at this point, taking a deep breath and assuring myself that I wasn’t as stupid as I felt, and pushed through the scrub knowing full well there would be no tracks or easy routes to follow.

At first it was easy enough, but as the slope began to quickly draw me down, I entered thickets of ferns that made it impossible to see where I was placing my feet. Minutes later, the ferns were joined by the dreaded lawyer vine, whose thin, strong, leafless tendrils snake their way through the scrub ready to tear a gash in any exposed flesh or send you tumbling over.

In places the vines leap from shrub to shrub, creating impenetrable walls of spiky greenery, forcing me to back-track several times.

Given Neale’s exact route is unknown, my plan was to do a loop, heading in via the valleys and streams and back by the ridge-tops, both of which posed their own unique obstacles.

In the creek, lined by small cliffs, there was little if any scrub, but the slimy rocks make for slow going, while the ridges, covered with spiky shrubs and finishing with, at times, impassable drops into valleys below, were no easier.

Despite being well equipped with food, water, map and compass, I struggled to move much more than a kilometre an hour.

I fell several times, tripped by vines, slipping on wet rocks or dropping down when a piece of rotting tree trunk gave way. Thankfully I didn’t sustain an injury, but in this rugged area, it could so easily have happened.

Within minutes of leaving the track, mobile phone reception was lost, and moving deeper down into the valley I never regained it. The only way to get help would be with a personal distress beacon, known as an EPIRB, which uses satellites to notify authorities. Twice I heard helicopters fly past, once directly overhead, but no matter how hard I tried to look through the thick canopy I couldn’t see them, let alone signal as Neale would so desperately have been trying to do.

The sceptics may question how someone could remain lost so close to civilisation, for such a long time, but the incredible isolation, the remoteness becomes apparent.

At times the canopy opened up slightly, giving glimpses of the impenetrable wall of cliffs circling the valley. The one visible gap to those great slabs of towering sandstone is to the south, towards the area where Neale eventually stumbled on two startled bushwalkers at Medlow Gap on Wednesday.

Perhaps it was these glimpses that led him to push on in that direction until help was found.

As I walked I tried to keep an eye out for the leaves and seeds that had become Neale’s humble meals, giving him a tiny boost of nutrients. They were few and far between, with many of the native grasses bare of seeds, not in flower or already raided by the menagerie of native animals that call the area home.

In the creek I was unable to find the leafy green plant Neale had nibbled on, or much else that resembled food, no matter how desperately hungry he would have been.

In contrast, water was plentiful. The terrible wet weather that had so hampered the search for Neale, preventing the use of helicopters for several days, had left the ground sopping wet.

Even tiny streams had a small trickle of fresh water gurgling between mossy boulders, a trickle that probably saved his life.

By 4pm darkness was starting to fall. The sun hid behind the rocky precipice of Narrowneck Plateau and, on cue, a cool wind began to roar through the trees, providing an eerie hum that lasted throughout the night.

On both sides of the creek, cliffs rose up to 30m high, with several small waterfalls tumbling down. After eventually finding a camp site, I started a fire – a luxury Neale never enjoyed – set up a tent and unrolled a warm sleeping bag.

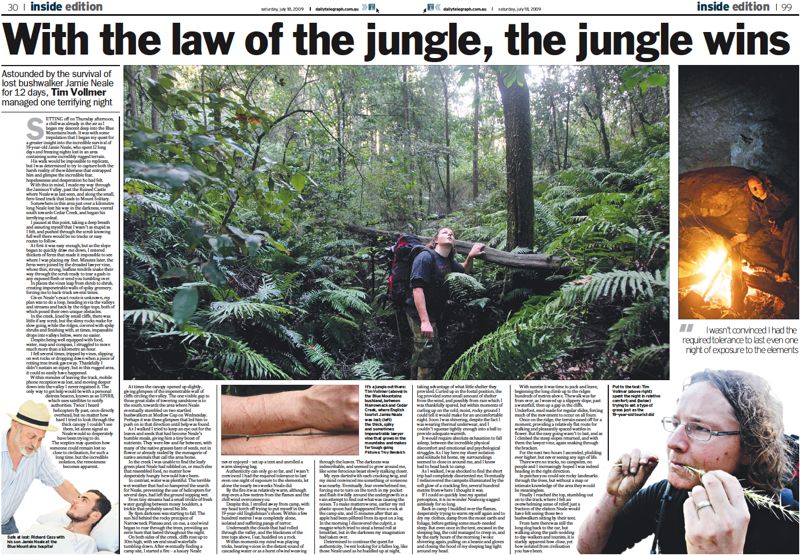

Authenticity can only go so far, and I wasn’t convinced I had the required tolerance to last even one night of exposure to the elements, let alone the nearly two weeks Neale did.

By the fire it was relatively warm, although step even a few metres from the flames and the chill wind overcomes you.

Despite this, I strolled away from camp, with my head torch off trying to put myself in the 19-year-old Englishman’s shoes. Within a few hundred metres I was completely alone, isolated and suffering pangs of terror.

Underneath the clouds that had rolled through the valley, and the blackness of the tree tops above, I sat, huddled on a rock.

Within moments my mind was playing tricks, hearing voices in the distant sound of cascading water or as a burst of wind weaving through the leaves. The darkness was indescribable, and seemed to grow around me, like some ferocious beast slowly stalking closer.

My eyes darted with each cracking twig, and my mind convinced me something or someone was nearby. Eventually, fear overwhelmed me, forcing me to turn on the torch in my pocket and flash it wildly around the undergrowth in a vain attempt to find out what was causing the noises. To make matters worse, earlier my red plastic spoon had disappeared from a rock at the camp site, and 15 minutes after that an apple had been pilfered from its spot on a log.

In the morning I discovered the culprit, a magpie which tried to steal a bread roll at breakfast, but in the darkness my imagination had taken over.

Determined to continue the quest for authenticity, I went looking for a fallen log, like those Neale used as he huddled up at night, taking advantage of what little shelter they provided. Curled up in the foetal position, the log provided some small amount of shelter from the wind, and possibly from rain which I was thankfully spared, but within moments of curling up on the cold, moist, rocky ground I could tell it would make for an uncomfortable night. Soon I was shivering, despite the fact I was wearing thermal underwear, and I couldn’t squeeze tightly enough into a ball to provide adequate warmth.

It would require absolute exhaustion to fall asleep, between the incredible physical discomfort and emotional and psychological struggles. As I lay here my sheer isolation and solitude hit home, my surroundings seemed to close in around me, and I knew had to head back to camp.

As I walked, I was shocked to find the short trip had completely disoriented me. Eventually I rediscovered the campsite illuminated by the soft glow of a crackling fire, several hundred metres from where I thought it was.

If I could so quickly lose my spatial perception, it is no wonder Neale zig-zagged aimlessly for so long.

Back in camp I huddled over the flames, desperately trying to warm myself again and to dry my clothes, damp from the moist earth and foliage, before getting some much-needed sleep. But even once in the tent, encased in the sleeping bag, the cold managed to creep in, and by the early hours of the morning I woke shivering again, pulling on a beanie and gloves and closing the hood of my sleeping bag tight around my head.

With sunrise it was time to pack and leave, beginning the long climb up to the ridges hundreds of metres above. The walk was far from over, as I weaved up a slippery slope, past a waterfall, then up a gap in the cliffs.

Underfoot, mud made for regular slides, forcing much of the movement to occur on all fours.

Once on the ridge, the terrain eased off for a moment, providing a relatively flat route for walking and pleasantly spaced wattles in flower. But the easy going wasn’t to last, and as I climbed the steep slopes returned, and with them the lawyer vine, again snaking through the bracken.

For the next two hours I ascended, plodding ever higher, but never seeing any sign of life.

There were no tracks, no campsites, no people and I increasingly hoped I was indeed heading in the right direction.

In patches you could see rocky landmarks through the trees, but without a map or intimate knowledge of the area they would be meaningless.

Finally I reached the top, stumbling out on to the track, where I felt an overwhelming sense of relief; just a fraction of the elation Neale would have felt seeing those two bushwalkers sitting by their tent.

From here there was still the long slog back to the car, but walking along the path nodding to day-walkers and tourists, it is starkly apparent how close, yet how isolated from civilisation you have been.